Como a mudança climática está deixando os países ricos mais ricos, e os pobres mais pobres

A temperatura está aumentando no mundo como um todo, mas as consequências disso não são as mesmas para todos os países.

A temperatura está aumentando no mundo como um todo, mas as consequências disso não são as mesmas para todos os países.

No último século, a mudança climática aumentou a desigualdade entre as nações, puxando para baixo o crescimento econômico dos países mais pobres e aumentando a prosperidade de alguns dos países mais ricos do planeta, aponta uma nova pesquisa.

O abismo entre as nações mais pobres e as mais ricas do mundo é 25% maior do que seria sem o aquecimento global entre 1961 e 2010, diz um estudo da Universidade de Stanford, na Califórnia.

Países tropicais africanos foram os mais afetados- os Produtos Internos Brutos da Mauritânia e do Níger estão 40% menores do que estariam se as temperaturas não estivessem aumentando progressivamente.

O Brasil, que é nona maior economia do mundo, teria tido um crescimento 25% maior se não houvesse aquecimento global.

Leia completo em BBC.

Permafrost collapse is accelerating carbon release

The sudden collapse of thawing soils in the Arctic might double the warming from greenhouse gases released from tundra, warn Merritt R. Turetsky and colleagues.

The sudden collapse of thawing soils in the Arctic might double the warming from greenhouse gases released from tundra, warn Merritt R. Turetsky and colleagues.

This much is clear: the Arctic is warming fast, and frozen soils are starting to thaw, often for the first time in thousands of years. But how this happens is as murky as the mud that oozes from permafrost when ice melts.

As the temperature of the ground rises above freezing, microorganisms break down organic matter in the soil. Greenhouse gases — including carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide — are released into the atmosphere, accelerating global warming. Soils in the permafrost region hold twice as much carbon as the atmosphere does — almost 1,600 billion tonnes1.

What fraction of that will decompose? Will it be released suddenly, or seep out slowly? We need to find out.

Current models of greenhouse-gas release and climate assume that permafrost thaws gradually from the surface downwards. Deeper layers of organic matter are exposed over decades or even centuries, and some models are beginning to track these slow changes.

But models are ignoring an even more troubling problem. Frozen soil doesn’t just lock up carbon — it physically holds the landscape together. Across the Arctic and Boreal regions, permafrost is collapsing suddenly as pockets of ice within it melt. Instead of a few centimetres of soil thawing each year, several metres of soil can become destabilized within days or weeks. The land can sink and be inundated by swelling lakes and wetlands.

Read More at Nature

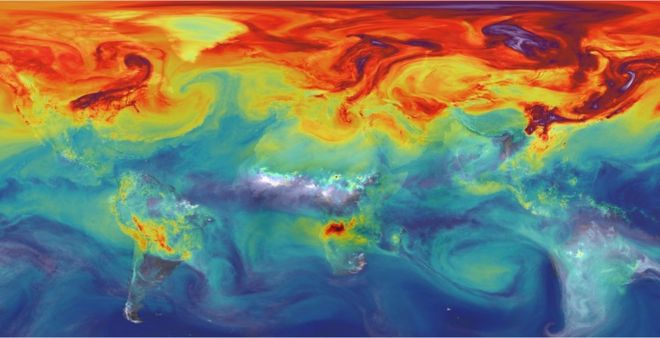

Nasa instrument heads to space station to map CO2

Nasa has sent up an instrument to the International Space Station (ISS) to help track carbon dioxide on Earth.

Nasa has sent up an instrument to the International Space Station (ISS) to help track carbon dioxide on Earth.

OCO-3, as the observer is called, was launched on a Falcon rocket from Florida in the early hours of Saturday.

The instrument is made from the spare components left over after the assembly of a satellite, OCO-2, which was put in orbit to do the same job in 2014.

The data from two missions should give scientists a clearer idea of how CO2 moves through the atmosphere.

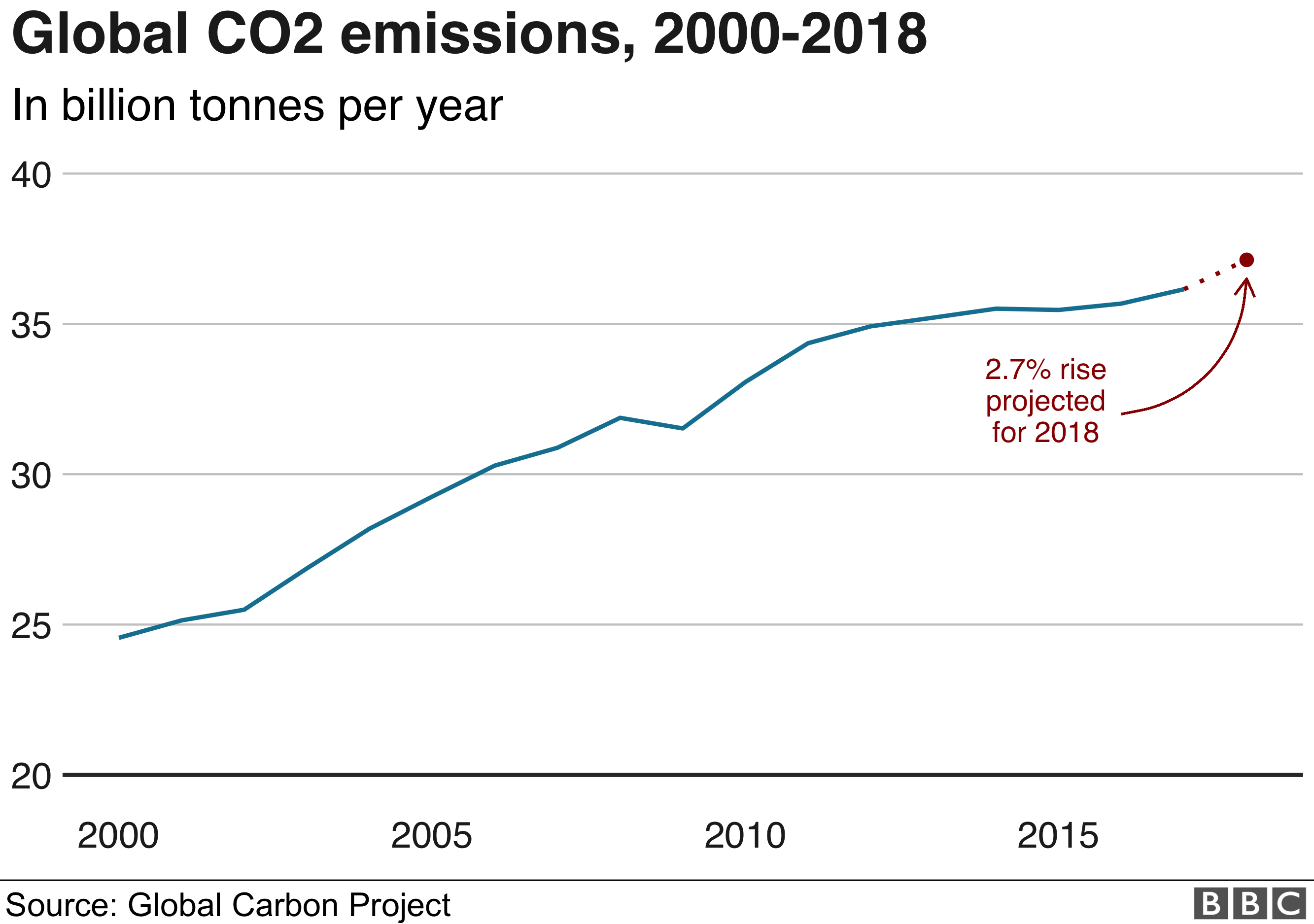

- CO2 emissions reach 'all-time high'

- Nasa mission 'watches Earth breathe'

- UK 'can cut emissions to nearly zero'

One way this will be achieved is through the different perspectives OCO-2 and OCO-3 will get.

The former flies around the entire globe in what's termed a sun-synchronous polar orbit, which leads to it seeing any given location at the same time of day.

The latter, on the other hand, because it will fly aboard the station, will only see locations up to 51 degrees North and South; and see them at many different times of day.

That's interesting because plants' ability to absorb CO2 varies during the course of daylight hours. OCO-3's dataset will therefore have much to add to that of its predecessor.

"Getting this different time of day information from the orbit of the space station is going to be really valuable," Nasa project scientist Dr Annmarie Eldering told BBC News.

"We have a lot of good arguments about diurnal variability: plants' performance over different times of day; what possibly could we learn? So, I think that's going to be exciting scientifically."

Read more at BBC

Mais itens...

- Parlamento britânico é o primeiro do mundo a declarar “emergência ambiental e climática”

- Entrevista do Mês: Eduardo Assad

- Cientistas discutem devastador custo da ação humana no planeta

- Novo ciclone atinge Moçambique seis semanas após o primeiro; ONU pede mais apoio

- NASA revela novas (e preocupantes) evidências do aquecimento global

- As chuvas extremas do Rio são a nova normalidade do clima?

- Temporais fazem parte de uma nova realidade, diz climatologista

- Motivo de caos no Rio, chuva anormal para outono é 'retrato de clima mais hostil'

- Humanidade consome recursos da Terra a taxas insustentáveis, alerta agência da ONU

- A diferença entre os impactos de um aquecimento de 1,5˚C ou 2˚C no planeta

- Emissões de carbono quebram o recorde em um retrocesso global devastador

- Demanda por energia dispara em 2018 e emissões batem recorde

- Situação do clima em 2018 mostrou aumento dos efeitos da mudança climática, diz relatório

- Reflexos do aquecimento global para a economia brasileira

- Falta de acesso à água afeta bilhões e provoca aumento de conflitos no mundo, diz relatório da ONU

- Terceiro Relatório de Atualização Bienal do Brasil

- Convite: Lançamento do Livro – Brasil: um futuro sustentável

- Artigo: A felicidade traz prosperidade

- Rio de Janeiro registra as temperaturas médias mais altas em 97 anos

- Biodiversidade é uma potência ainda subaproveitada no país.

- ‘Estresse térmico’ deixa pessoas mais nervosas nos dias quentes

- Groenlândia está derretendo mais rápido do que esperávamos e não há muito mais o que fazer

- Verão pode causar 'estresse térmico' no corpo

- Gelo da Antártica está derretendo seis vezes mais rápido do que há 40 anos, diz estudo

- 'A proteção do meio ambiente não pertence a nenhuma corrente política ou ideológica'

- Aquecimento dos oceanos ocorre em ritmo mais rápido que o esperado

- Verão tem temperaturas mais altas que as do ano passado; tendência é esquentar

- Agro holandês é POP

- Animais silvestres em perigo: projeto de lei libera caça no Brasil, também em unidades de conservação. E muito mais!

- Chuvas torrenciais e muito calor: o que determina o clima das grandes cidades?

- Verão de 2019 vai ser escaldante e já sabemos qual mês será o pior

- Ministério do Meio Ambiente oferece 8 cursos na área socioambiental

- Agenda do Evento de Lançamento do Relatório "Potência Ambiental da Biodiversidade: um caminho inovador para o Brasil"

- COP 24 aprova 'livro de regras' do Acordo de Paris

- Relatório encomendado pela própria UNFCCC sobre o aquecimento

- Secretário-geral da ONU alerta que planeta não pode se permitir fracassar na COP 24

- Brasil perderá se sair do acordo climático, diz ex-negociador dos EUA

- 1. SBPC se manifesta contra a saída do Brasil do Acordo de Paris

- A COP24 em Katowice terminou neste domingo, por volta das 00:30h.

- Artigo: Capitalismo climático Para a obtenção do lucro, é fundamental que se limite o aumento de temperatura da Terra

- Painel Brasileiro de Mudanças Climáticas e a Fundação Grupo Boticário lançam Sumário para Tomadores de Decisão sobre biodiversidade e clima na COP24

- Relatório Especial “Potência Ambiental da Biodiversidade: um caminho inovador para o Brasil”

- 1º Fórum Brasileiro de Transição Energética

- Evento de Lançamento do Sumário para Tomadores de Decisão (STD) do PBMC e BPBES – Espaço Brasil na COP-24

- COP24 "Eles chegaram a Katowice de bicicleta"

- Como anda a COP14 da Biodiversidade?

- Moving for Climate NOW

- 2018 UN Biodiversity Conference

- Primeira chuva no Atacama em 500 anos destrói vários micróbios

- Temperatura do planeta poderá aumentar 3,2 graus Celsius, muito além da meta de 1,5

- Biodiversidade é 'galinha de ovos de ouro' desperdiçada no Brasil, mostra relatório

- Impacto das mudanças climáticas intensificam incêndios na Califórnia

- Biodiversidade não é problema, é solução

- BRASIL pode ser líder em desenvolvimento sustentável, dizem cientistas

- Aquecimento climático em São Paulo já é o dobro da meta global

- Não é só pelo 1,5ºC

- Chamada pública "Boas práticas de sustentabilidade A3P"

- Ministro divulga nota sobre fusão com o MAPA

- Fome: aquecimento aumenta o risco de uma nova grande crise global

- Populações de animais caíram 60% em 44 anos, alerta WWF

- Anúncio da fusão dos ministérios da Agricultura e Meio Ambiente preocupa a Coalizão Brasil

- Remote Hawaiian Island Wiped Off The Map

- Dados do Inpe sugerem aceleração da área desmatada na Amazônia

- O que precisa ser feito em cada setor para limitar o aquecimento global em 1,5oC?

- 1,5°C a mais até o fim do século - otimismo possível?

- O Brasil e a biodiversidade

- Aquecimento global está acima da meta, diz IPCC

- Análise: Relatório do IPCC força aquecimento global sobre agenda dos candidatos a presidente

- ONU dá último alerta para evitar a catástrofe climática

- Educação ambiental abre 16 mil vagas

- 37 things you need to know about 1.5C global warming

- We have 12 years to limit climate change catastrophe, warns UN

- Leaked US critique of climate report sets stage for political showdown in Korea

- Aquecimento global pode modificar eixo de rotação da Terra, aponta estudo da Nasa.

- Mobilidade elétrica na cidade: Veículos Coletivos e de Carga

- Aquecimento eleva risco de desertificação no Nordeste

- DERRETIMENTO DO PERMAFROST ESGOTA O ORÇAMENTO DE CARBONO ANTES DO PREVISTO

- Ações para reduzir emissões na agricultura ainda não são suficientes Este trecho é parte de conteúdo que pode ser compartilhado utilizando o link https://www.valor.com.br/agro/5852317/acoes-para-reduzir-emissoes-na-agricultura-ainda-nao-sao-suficientes o

- IV ENPJA ocorre em setembro

- Abordagens metodológicas para análise de Vulnerabilidades à Mudanças Climáticas

- A Cidade Universitária e o Consumo de Energia - Hoje

- Marcha pelo clima reúne mais de 30 mil pessoas nos EUA.

- Mobilização global ‘Una-se pelo clima’ realiza ações em mais de 90 países

- Navio bate em ponte e aeroporto fica isolado na passagem do Tufão Jebi no Japão

- NASA Discovers Bubbling Lakes In The Remote Arctic - A Sign Of Global Warming

- Elevação das concentrações de carbono na atmosfera ameaça a nutrição humana

- O aquecimento global já é realidade. E agora?

- Merkel diz ser contra novas metas de redução de emissão de gases na Europa

- XIII UFRJ AMBIENTÁVEL - Semana Acadêmica da Engenharia Ambiental

- A Professora e cientista Suzana Kahn participou do evento "Foco nos setores de Energia Elétrica e Petróleo e Gás", promovido pela Siemens.

- A Cidade Universitária e o Consumo de Energia

- Kofi Annan, Who Redefined the U.N., Dies at 80

- NASA releases time-lapse of the disappearing Arctic polar ice cap

- Árvores revelam evolução da poluição ambiental em São Paulo

- Presidente eleito terá de retomar trilha da responsabilidade climática e enfrentar retrocesso

- Heat: the next big inequality issue

- Mudança climática está matando os cedros do Líbano

- Céticos do clima devem pedido de desculpas a quem acreditou neles

- Uma fornalha chamada Terra

- Coletivo urbano está à beira do colapso